Once I was alerted to the concept of “hard fun” I began listening for it and heard it over and over. It is expressed in many different ways, all of which all boil down to the conclusion that everyone likes hard challenging things to do. But they have to be the right things matched to the individual and to the culture of the times. These rapidly changing times challenge educators to find areas of work that are hard in the right way: they must connect with the kids and also with the areas of knowledge, skills and (don’t let us forget) ethic adults will need for the future world.

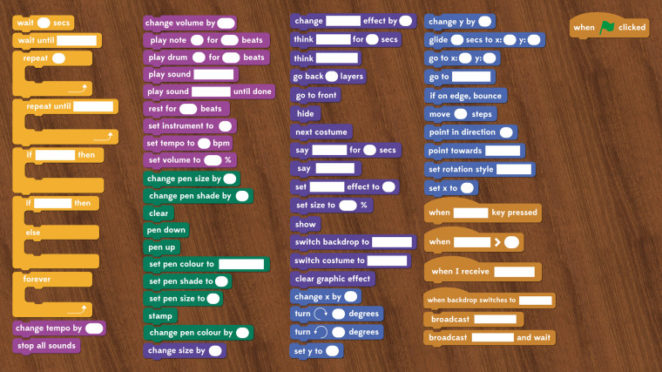

Student voice and choice has proven to be crucial for learning. Often though, choices are too vague for students to decide a course of action or direction. In my mind, plopping students in sandbox tools like Scratch allows for a great integration of both choice and voice while allowing the teacher to provide some direction. For example, asking students to program a Mother’s Day greeting card provides many opportunities for students to make choices while still following specific instructions. Student choice doesn’t always have to mean “whatever you want” but instead can mean “whatever you want within these parameters.” Too much choice only creates problems for many who are unable to filter through options independently without a prior schema of the activities. After all, we don’t learn from experience, we learn from reflection on experiences.

Here are three ways to engage students with hard fun:

1. Unplugged Coding

Have you seen the printable code blocks from both Scratch Jr. and Scratch? These transparent images are perfect manipulatives to have students write scripts on an interactive whiteboard. Classmates can follow along from their seats, try the script and provide feedback to the students at the front. Other options include creating scripts that contain bugs, projecting them to the IWB and having students try to debug in realtime. Immediate feedback from the environment intrinsically motivates students to want to solve the puzzle. Games are challenging and games are rewarding. This experience would be very similar and certainly “hard fun.”

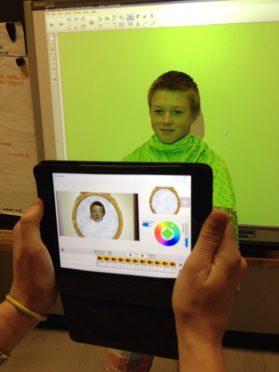

2. Green Screen Public Service Announcements

Perhaps you are studying body image or bullying in health class. By combining green screens apps with the IWB, students can seamlessly swap backgrounds to add different scenes quickly. While the task might be to create a PSA to inform younger students about an issue, the choice of scene, tool, background and content not only engages students but makes them invest in their learning. A bi-product of the process of making a piece of media is exploring the tools to carry it out. Students would engage in “hard fun” while demonstrating other 21st century competencies like creativity, collaboration, problem solving and organization.

3. Making With Minecraft

Minecraft. Need I say more? I love having students create structures in Minecraft that represent scenes from stories they are writing about. By providing students an opportunity to orally tell a story while navigating a Minecraft town they have created, word choice improves. I have used Minecraft as a means to organize ideas, develop characters and allow students an opportunity to bring ideas to life prior to the writing process. A bat is now a ‘scary bat’ when we visualize it in the game. Encouraging students to write adjectives to describe what they see and have built will certainly improve their writing. We love connecting our tablets to the projector to share our creations on our SMART Board because it allows everyone to see, share, and be involved in the design thinking process. Perhaps most importantly, the ability to annotate over a Minecraft visual is powerful!

The Evaluation Process

Assessment is easy. Providing kids realtime descriptive feedback keeps the learning process in full throttle. However, quantifying these experiences is a big challenge. How can you evaluate creativity?

With these kind of sandbox ideas, we are forced to rethink what it means to fail at school. “Hard fun” means things don’t always go well the first time through. As Papert states in Mindstorms, you almost never get it right the first time when programming a computer.

The question to ask about the program is not whether it is right or wrong, but if it is fixable. If this way of looking at intellectual products were generalized to how the larger culture thinks about knowledge and its acquisition we might all be less intimidated by our fears of ‘being wrong.’

– Seymour Papert (1980)

For all the kids who grow up in a small town and think they don’t stand a chance. You do. I was once that kid.

For all the kids who grow up in a small town and think they don’t stand a chance. You do. I was once that kid.